| RAF Feltwell - Personnel - memorial pages. |

Photo pages -> |

|||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||

| Recollections | RAF Feltwell History | RAF Feltwell Planes & Buildings | 75 NZ Squadron |

|

|

|

|

|

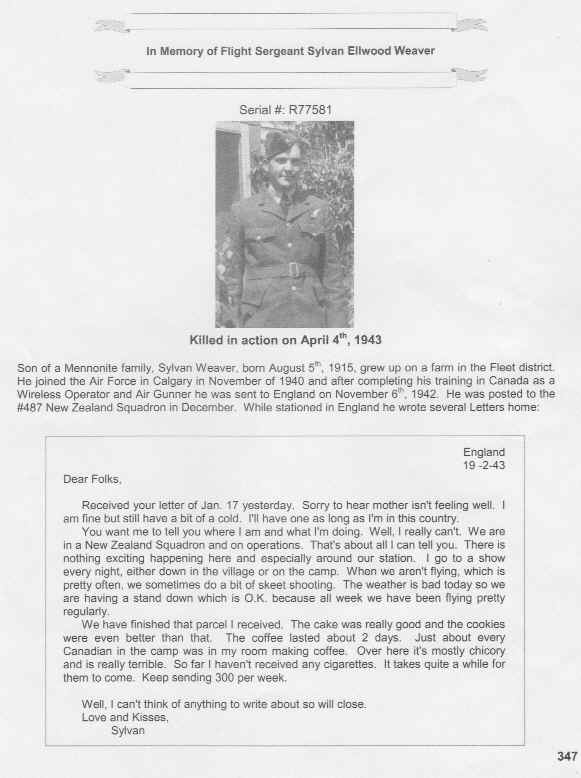

Memoir for Sylvan Ellwood Weaver Born August 5, 1915. Killed in action April 4, 1943.

Written by Larry Weaver (his younger brother Armand’s son)

So, because Sylvan did not write his own autobiography, nor could he tell any details after he died, I only have stories my Dad told me, actual letters Sylvan wrote home after being posted in England, and military records by which to put forth this memoir. I am not a writer by any stretch of the imagination but, I like you (the reader) have an imagination. When I read a story or watch a movie, I get immersed in the story and cannot tell the difference between me and the character I am reading about. In my imagination we are the same person. So, based on this I will write it in the first person as I imagine Sylvan would have felt. So, in some ways, it is a bit like a novel when I write as if I can feel like he felt and truer perhaps than when I write just the military facts recorded. Also, I do have the same DNA so a lot of my feelings and thoughts will be the same, for example, I am quite sure our senses of humour are much the same. I can still have a good laugh today from this story Dad told us about Sylvan: They were driving down the road in their car of that time - perhaps a Model A. Grandpa was driving and Dad and Sylvan were in the back seat. Sylvan pipes up, “Dad, can you drive any faster?" Grandpa replies, "No, son. Why do you ask?" “Well, there's a guy behind us pushing a wheel barrow, and he's trying to pass us!"

As I write in the first person, I - Larry will type it l(S) so you will know it is what Sylvan thought or felt as I imagined he would. When I write things that I am feeling or thinking I will write them as I(L)

So, l(L) think that every human ever born regardless of race or colour, family or religion, has pretty much the same basic human needs i.e. to feel needed, loved and safe. When that is interrupted it shocks us. l(S) felt that way also. l(S) just wanted life to be safe. So, at the age of six I got a major shock. First of all, my younger brother was born. That was different but felt good. It felt kind of nice actually. What was shocking about it was that Mom was sick for four months and then the real blow hit. She died! Was it my (S)'s fault? Where did she go? They told me she went to heaven to be with God. But where was God? Was he up in the sky? Could she come back out? Back to the ground where she could keep me safe? Daddy couldn't stop crying. My older sister, Reta couldn't stop crying. She had to look after me. But she wasn't my Mom! And she was only 8. I was six and baby Armand was four months. For sure Reta could not look after a baby. So, Dad sent Armand away to live with some relatives in Didsbury who were unable to have children. What a shock! I no longer had my Mom - she was up in heaven and I didn't have my brother. How was he making out? I couldn't be consoled. So how could I have stopped this? It did seem somewhat my fault.

So, after a couple of years l(S) sort of forgot the shock. School took my mind off my little brother and my older sister Reta was doing pretty good at cooking and looking after me. Then Dad got interested in another German girl. I(S) have no clue how they got together but Dad was happy and my sister was even happier because someone else could take over cooking and housework. A few months on, they got the idea that maybe they. could get Armand repatriated. It had been long enough that Dad (Dave - Sylvan's Dad) thought Armand would have forgotten him altogether, so he and my step-mom Hannah decided to go to Didsbury and see if Armand even remembered him. Luckily for me(S) as soon as Armand saw Dad, he dropped his toys, screamed out “Daddy” and went running to his arms. For me, this felt safe again. I(S) not only had a new mother but an estranged brother back again.

l(S) grew up to I8 yrs old and finished high school but was not off to college. I just had Junior Matriculation so definitely couldn't get more education. It was 1939 and Armand had gone off to university in Edmonton to study Medicine. That was how he dealt with Mom's unnecessary death by learning about how to save women after they had given birth. I suppose he carried a great deal of guilt thinking that it was his birth that caused her death. That was true I guess but those are bigger matters in our Creator's hands. Not something we humans have much say in. I'd been working for various farmers, had tried working at an elevator for three months but that wasn't my cup of tea. Even tried being a painter for a year but that didn't seem to be going anywhere. In September of '39 Canada entered World War 2. By then sister Reta was dating a guy and threatening marriage. Here I was 24 and still calling Castor my home. When I was 25, Reta left home in 1940 to marry Bob Holloway. Now there was just Dad, Hannah and me! Was I carrying my weight to support the family?

So that question of safety and being needed/useful came back to haunt me again. How can I feel useful at just 25 hanging around home, uneducated, no girlfriend, not much education, no steady job, broke most of the time and eating up Dad's hard-earned money? The answer seemed pretty obvious when the Canadian government was trying to entice young men into the services. Of course, I talked it over with Dad and Mom. They said it was totally up to mc. So, my six-year-old mind(S) came up with the idea to go flying into the skies like Momma had done. (I(S) know that sounds pretty preposterous to you but that's how my child's mind worked.) The writing was on the wall and I headed to Calgary to take steps to enlist in the Air Force.

I(S) went down to Calgary in June of 1940 to start the process. I couldn't believe that they wanted perfect specimens so to speak. Like you'd think they would take just about anyone as long as they could walk! Well, that's my(S) sense of humour kicking in again. I stayed in the Empire hotel in Calgary while getting some of the testing done. That's where all the guys who wanted to enlist stayed while being tested and inspected. Like it took from June of '40 until Nov. 23 until I could see my name there on the forms. And if there's anyone today who thinks signing up for the military is a joyride, I'll let you in on the next shock to me after enlisting. Five days later I had to make up my will! Yup, all the guys did. You didn't enlist thinking that you'd be a war hero and live to some ripe old age. You weren't in this thing by yourself. You were in it with literally thousands of other guys from all across Canada. There wasn't a lot of glory to be passed around let me tell you. But I did feel I was getting an education that was special. And all the guys willing to enlist were doing something for their family, the whole of Canada. That in itself was quite a feeling.

Now, as I(S) said before, I didn't record any of this stuff. This is where my nephew comes in. He had the family stories but he didn't have the facts around my soldier life. These were recorded by the Government of Canada on 25 sheets/cards. l(L) had to find them (on the internet - actually you could too) but then interpret the gibberish recorded on them into a story that made sense. They didn't just write down things like: enlisted and went to Brandon. No, they had to complicate it by making it simple! How did they do that? Well I(L) looked (on the internet again) for the Military's book of abbreviations. Yes! A book of 189 pages to be exact! And how simple would it be to read this book? I’ll give you an example: D.R.O. - District Recording Officer or Divisional Routing Order or District Routine Orders or Daily Routine Orders. So, you take your pick! Luckily for me (L) I had studied Mandarin Chinese where there is no conjugation of verbs, so you just have to figure out tenses (past. present, future) from context. Most D.R.O.'s refer to Divisional Routing Order.

Before I(L) get into actual training, I'd like to share some of Sylvan's medical and personal history. I don't think he'd mind.

I(S) felt in really good health. In spite of this, I(L) can't figure out why Sylvan was hospitalized 4 times? Twice in the Colonel Belcher in Calgary, once in the University hospital in Edmonton, and once in the Station Hospital. To actually get to the hospital and be enlisted a S.L.T.W. - Special Leave Travel Warrant would need to be issued. I(L.) don't think you'd be transported in military ambulance to Emergency with sirens blaring, just maybe an unceremonious, bumpy ride in an army jeep or those big 5-ton trucks you see. Then according to military recorded abbreviations, you would be S.O.S. that stood for Struck off Strength/discharged from that unit. Then when you entered the hospital you would be enlisted. Then, e.g. if you were discharged from hospital but went back to your military unit/school, you would be T.O.S. i.e. Taken on Strength. Go figure. One of those weird abbreviations was MFB227 that stood for Medical History of an Invalid! Maybe you felt a bit worse for wear after a ride in one of those improvised ambulances? That was a shock to me(L). In one of my(S) letters home in '42 or '43 l(S) said that my operation was okay. So, maybe it was something like appendix or gall bladder? Something that took me two weeks to recover from. Still, not something that would improve in a bumpy ambulance ride! Then again, if the ambulance was anything like Dad's car, it would be going slow enough for wheel barrows to have passed!

I had a few vices contrary to my Mennonite upbringing. The most obvious one was that I smoked. Just 10 cigarettes per day. This bothered me in that it was offensive to my family but it did help me feel more calm and relaxed - safer, especially when we were flying in operations into Holland. It helped me cope with some of the shocks in life like scares, sickness, deaths, secrets (of the military kind) etc. You will see that my(S) folks were sending me 300 cigarettes per week, and Armand was sending 300 soon. This would do me a month at 10/day but I was sharing them with all the Canadians in the squadron. I didn't drink thank goodness, perhaps because it was more offensive even than smoking, plus I couldn’t really afford it. I'd have to be an alcoholic to feel good/safe on a continual basis and for sure, the military wouldn't allow that!

Maybe the navy would allow drunken sailors but drunken pilots, navigators, bombers and air gunners? I don't think so - maybe just in port. But not on a 24hr basis.

I liked baseball, hockey, and hunting. My records say that I was a pretty good shot. Course that was just on my word. Later on in training I proved I was a good shot on moving targets. I did receive an Exemplary Gunner's proficiency badge and it was recommended I be a W.O. (Wireless Operator) and A.G. (Air Gunner).

When the war broke out in Europe, Britain had the enemy at its doorstep so speak, so that is why training schools were set up in Canada. They couldn't very well do training in airspace outside Britain because the Germans were there. In Canada there was excellent flying conditions for flying, immediate access to American industry i.e. parts and aircraft, and could transport men and airplanes to England via the North Atlantic. So, under the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan. signed Dec. 17, 1939 these schools were set up across Canada. Pilots would come from England, Australia, New Zealand and Canada to train under this umbrella. The plan's objective was to train pilots, navigators, bomb aimers, wireless operators, air gunners and flight engineers. As a result, 131,000 air crewmen including French. Czechs, Norwegians, Poles, Belgians and Dutch were trained between 1939-1945 making this one of Canada's great contributions to Allied victory. U.S. president Roosevelt called Canada the "aerodrome of democracy.”

There were 107 training schools across Canada. Each focused on specific skills: flying, bombing and gunnery, air observation, air navigation, radio operations, or flight engineering. I(L) suppose that if you were good in all departments that if one got injured or killed while flying that maybe you could jump in and fill the position? That's just a guess. Trainees began their training at a Manning Depot where they learned to bathe (can you imagine needing to Iearn this?!!), shave, shine boots, polish buttons, maintain their uniform, and behave properly. The latter sounded pretty English to me (S). Like did you have to hold your fork in your left hand and knife in your right? This was humorous to me. Like how ridiculous can you get? Would I be a better soldier with better manners? LOL as they say these days in computer talk. We also received two hours of physical education daily and instruction in marching, rifle drill, foot drill, saluting and other routines.

So I(S) was first sent to Brandon, Manitoba - a Manning Depot. After one month it was decided l(S) would make a good W.A.G. Wireless Air Gunner so was sent directly to Medicine Hat, a service training flying school (S.F.T.S). Here we in bomber, coastal or transport command would train in twin engined Cessna Cranes and Avro Arsons. Cessnas were a pleasure craft made in Kansas that were produced to keep up with demand. The Ansons were a British made military craft quite a bit faster than the Cranes. Instructors for the most part were civilians. For the first eight weeks we were part of an intermediate training squadron; for the next six weeks an advanced training squadron; and for the final two weeks at a bombing and gunnery school. It taught bomb aiming and aerial machine gunnery to air observers, bomb aimers and wireless air gunners. These areas required large areas of wilderness so to speak to accommodate bombing and gunnery ranges, so what better bald prairies than around Lethbridge and Medicine Hat?

April 26, 1942 I was transferred to #2 Wireless School Calgary. I wasn't there three weeks and got sent to hospital. It looks like it was just shy of 2 months I spent in hospital. Quite frankly I(L) can't imagine how I(S) learned anything. But I(L) am slowly figuring out that I(S) was actually in Calgary for over one year. Now these leave gaps are making more sense.

The actual school was located in the facilities of the Provincial Institute of Technology and Arts (PITA). This was located on 16 Ave. N. now occupied by SAIT, Calgary. Under the BCATP in 1940, plans were for four dedicated ‘Wireless Training Schools'. These provided facilities for training Wireless Operators in the operation and maintenance of radio equipment, both for ground based wireless stations and as a crew in aircraft, in actual flight conditions.

The main function of a Wireless Operator on a multi-engine aircraft during the War was to maintain contact with base stations using C.W. (Continuous Wave) Morse code. It was a great deal more difficult to send and receive code while airborne, than in stable, land-based stations. Airborne Wireless Training was a major part of the curriculum at each of the BCATP Wireless Schools.

To learn Wireless, I(S) a typical day looked like this: half an hour in a classroom, three and a half hours in simulator classroom (where we each could cram ourselves into a space similar to a real plane and send and receive code), and seven and a half hours in an actual plane doing what we had on the ground. At first in '41, these planes were 2-seater Tiger Moths. But they soon figured out they were too small for 2 men and heavy radio equipment so soon switched to Fort Fleets. But not before a Tiger Moth had crashed in training killing two airmen. That shocked me! The Fort Fleet's weren't that much better and eventually were replaced with American Harvards in '43. That's after I had graduated though. The subjects we learned were theory, Radio Equipment, Morse, Procedure, Signals Organization, Armament, Drills and Physical Training. There were 73 in my class and I placed 22, with a mark of 79.2%. Not something to boast about. We were taught at home to not be proud so I wouldn't have bragged anyway. Graduation day - May 25, '42 I was authorized to wear Wireless Operator's badge. Maybe it was my grade I(L) don't know, but May 28, ‘41 I was ranked as L.A.C. - Leading Aircraftman.

The day I(S) graduated; the records show I turned up in Lethbridge at #8 B.G.S - Bombing Gunnery School. Little did I(S) know it then it was the same place nephew Larry was to show up for his first job. If we had been able to get together then in ‘42 I'm sure we could have joked about the wind! E.g. If you lose your hat here don't bother chasing it. Just keep trying on hats as they blow past you until you find the right size!

The records show it was exactly a month spent here and it wasn't too intense. By that I(L) mean that it appears to be more theory than practical. On the written test l(S) got 77% on practical and oral test – 53%, and on Ability as a Firer 76%. On the practical side though I did actually fly a total of 12 hrs 20 min. in a Fairey Battle. These yellow monoplanes look a bit like a Harvard (more streamlined though). They have one .303 machine gun in the starboard wing and one Vickers ‘K' gun in the rear cockpit. To operate the gun, you would actually slide the cockpit back and stand up to shoot it. It could fire between 950 and 1200 rounds per minute. I(L) doubt the test ratings of the machine guns in the wings but Sylvan was rated on that. Another rating that’s undecipherable is rounds fired: ground - 196, air to ground – 160 and air to air 1800. I(L) don’t understand this either but will include it here in case some readers do. June 22, '42 I(S) was authorized to wear the Air Gunners Badge.

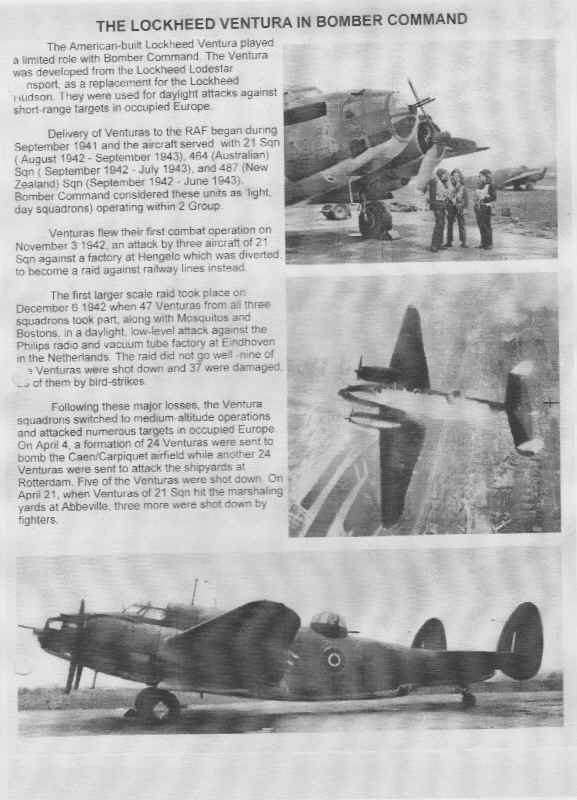

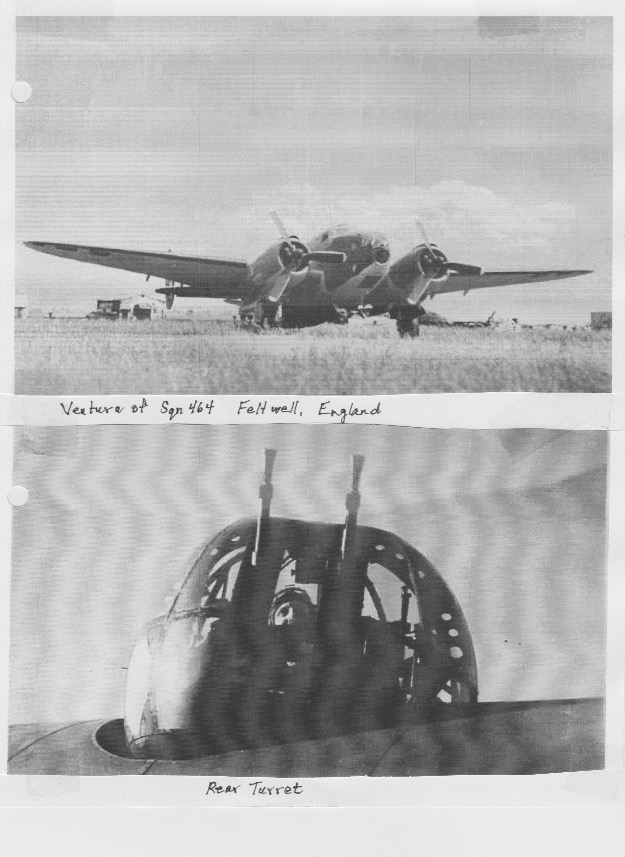

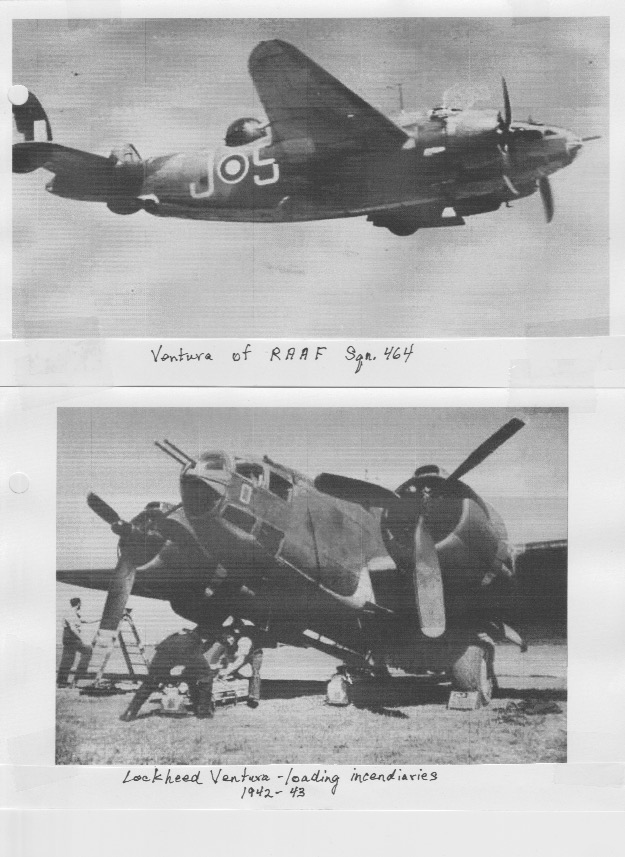

July 7, .42 I was assigned to #34 0.T.U - Operational Training Unit Pennfield N.B. The unit had just been transferred from Yarmouth, N.S. Of that year. Yarmouth was considered a better base for an operational and not a training unit at the time. By the time we arrived the base was just getting up and running and a lot of the protocol of running it as a training unit had not even been established yet. The airfield lacked the proper infrastructure to function as a training unit. It sorely lacked accommodation and 200 men were left behind in Yarmouth. This detachment was responsible for armament training that included gunnery and bombing. The separation of key training personnel deeply impacted the quality of our training. In addition to Venturas our Unit had various other aircraft. One of these was a Lysander whose primary use toeing gunnery targets for us practice shooting at. Problem was they were too slow and did not have proper towing gear! When we arrived however, some of these shortfalls were being resolved, however moral was low. Training was to include ‘ferry’ training that would enable pilot graduates to transfer our machines to England upon completion of our course. The only reason the faster Venturas were chosen is there was a limited quantity of the Hudson Bombers to train in at Pennfield.

This place couldn’t help but remind me of my Pennsylvania Dutch roots, close to St. Jacobs, Ontario where a great many Pennsylvania Dutch settled, and where my dear mother was born. It was chosen as an O.T.U. because of its similarity to the south of England where bomber units were stationed. It had a very low ceiling, was often foggy, similar to airfield in England sp. Feltwell and Methwold where we would be taking off from. This place wasn't without its problems though either. It was here that we were introduced to the Ventura twin-engined bombers. Over the course of training from '42 to the end of the war 59 airmen became fatalities at Pennfield i.e. they didn’t die in action, but in training!

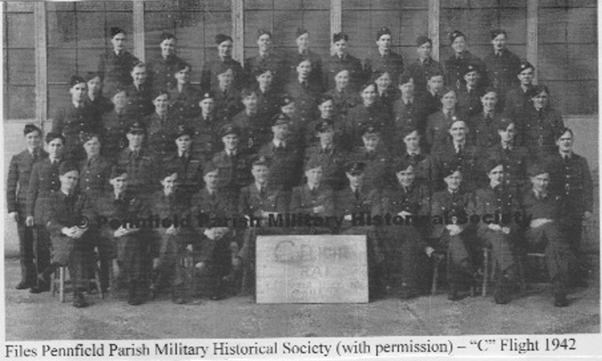

I(L) found the Course number 2 that Sylvan took. There were 60 airmen (our picture is on page 6 where you can verify me - I(S)’m the fifth from the right in the back row). There were 3 divisions of soldiers with two squads A & B for each division: Pilots, Observers or Navigators, and Wireless Operators/Air Gunners. There was twice as many Air Gunners as both Pilots and Navigators. Course 2 started July 20. '42 for Wireless Operators/Air Gunners and graduated October 10, '42. The Navigators graduated at the same time but they didn't start until Aug. 20. The scale of training for these four areas began to coalesce with the arrival of 54 Ventura 2 bombers between May and August of '42. These planes were dubbed the 'flying pigs’ because of their cavernous fuselage space. These Venturas had major maintenance issues, so much so, that by the time I(S) left in November '42, 18 B-25 Mitchell's were brought in and Venturas reduced from 54 to 39.

The program at Pennfield was designed over three phases. Conversion training (30 hrs), operations (35 hrs), and Armament (35 hrs) for a total of 100 hrs for pilots under training. Navigators and WAG’s (Wireless Air Gunners) received 70 and 78 total training while AG's 35 hrs at the armament phase only. Flying was only a small part of the training. Considerable time was given to ground lectures. Subjects included airmanship, army air, support, Bombing, Gunnery, Instructional Fuselage, Intelligence, Meteorology, Navigation, Operations Photography, Signals and Tactics. It varied by crew position. Instructors at O.T.U. 34 came from Greenock, Scotland. They were tour expired pilots rested from operations. Shocking to me (S) was the number of accidents here. It averaged 2.5 airframes per month and that meant our buddies were being killed right before our eyes! That induced the need for better aircraft. Well, these problems l(S) could do nothing about.

I(S) transferred out of there on Oct. 25, '42 and headed to the U.K. via an R.A.F. Trainees Pool in Halifax. This operation was something else to behold. From what I(L) can figure the November crossing of the North Atlantic was one of the largest. It involved 8 (Cruise ships converted to) troop carriers carrying 14,023 men. It took from Oct. 27 to Nov. 6 to get everyone on board and records filed. We all had to pass through the P.R.C. that's the Progress Review Committee to figure where we were all going. They had that strange way of record keeping where it said that I was T.0.S. i.e. Taken on Strength into the #3 P.R.C. They of course kept Canadians of the R.C.A.F. together so we could get to know the guys we would be in operations with. This was only outdone by the Queen Elizabeth cruise ship in 8/43 which carried 14.313 men across. No escort was needed upon embarkation, but 2 days out from port on the European side fighters would come alongside for protection. Life on board was pretty ho-hum. We needed some R&R but not much like a cruise in the Caribbean! In staterooms for two, 10 men were assigned and rooms for three got 15 men. This was pretty close-quartered but it was a good way to get familiar. This is where I got the low-down on what the weather would be like where we were going because Robert Steedman (pilot of our plane shot down) took his formal schooling in Nanaimo and Victoria. B.C. and he seemed to think weather was the same where we were headed. Most of the day was spent in long line ups for the two meals served per day. There wasn’t time enough for three meals anyway. Being on the ocean was brand new for me (S) but I didn't get seasick because we had experienced plenty of bucking around in planes in our training. Then when we arrived in England, we were S.O.S. Struck off Strength from #3 P.R.C. and T.O.S. to R.A.F. Royal Air Force Feltwell. Feltwell was the name of the base from which we would be flying the Ventura's. Luckily for me I missed Operation Oyster. That was the raid attacking Eindhoven in occupied Holland. That was a pretty impressive one actually even though there were some losses. I(S) was just as glad to miss it because it had been prepared for one month. This was the Philips factory where parts, sp. radar vacuum tubes were being made for radios and radar. This 'radar war had been going on since 1933 (in which anyone involved was sworn to solemn secrecy, so that included all airmen) and had progressed to the point in 1940 where England had 29 ground-based radar stations giving protection along its southern and eastern coasts against invading German bombers. What had not been produced yet was the implementation of radar sets on planes. This Philips plant located in Eindhoven Holland produced the majority of glass-based radio tubes used in the production of radar sets. 25,000 sets and 250.000 of the EF50 pressed glass bases were quickly manufactured in 1941 and sent to England factories making the radar sets literally hours before Germany flattened Rotterdam with bombs and Holland fell to their occupation. But now radar sets and the precious EF50 radio vacuum tubes would not be going to the German Reich.

Operation Oyster was a R.A.F. Operation/raid carried out with daytime medium bombers among which Venturas of #487 R.N.Z.A.F. (Royal New Zealand Air Force) were used (flying at low altitudes of 100ft for which they were not designed) so as not to kill Dutch civilians i.e. they could see what and who they were bombing and the Dutch could see them coming. In spite of this precaution, 150 civilians became casualties. As l(S) said I missed it by 10 days. It took place December 6, 1941 after a month of careful planning and training for it. I arrived in Feltwell December 3 but did not get T.O.S. (Taken on Strength) into Squadron #487 until December 16. Because I was not a part of the preparation and also not yet T.O.S. into Sqn. 487 I was not involved. I heard all about it though and how many planes were lost and 7 soldiers killed. Oh well, this was the reality of war.

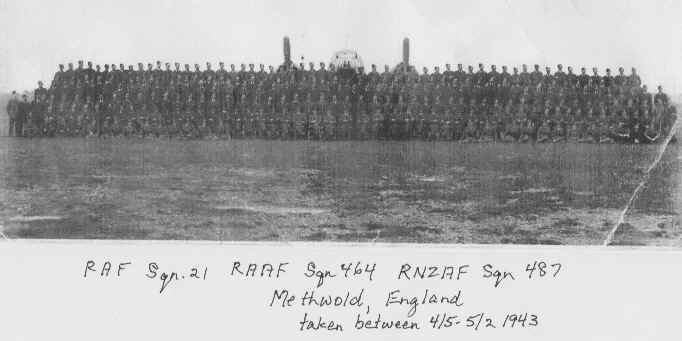

Our Squadron - R.N.Z.A.F. (Royal New Zealand Air Force) had just been formed Aug. 15, '42 and R.A.F. Sqn. #21 moved from Bodney to Feltwell to train our Sqn. #487 and Sqn. #464 of the Royal Australian Air Force. The R.A.F. Sqn. 21 was stationed at Methwold in the countryside 3 miles north of Feltwell. Don Palmer a local farmer there remembers the sudden influx or Aussies and New Zealanders. His Dad had managed a farm in Australia before the war, and when that fact became common knowledge at the camp, a lot of the airmen started visiting the farm. A lot of them had been farm boys so they showed up at milking time to help Don. Sometimes there were so many of them there were hardly enough cows to go around!

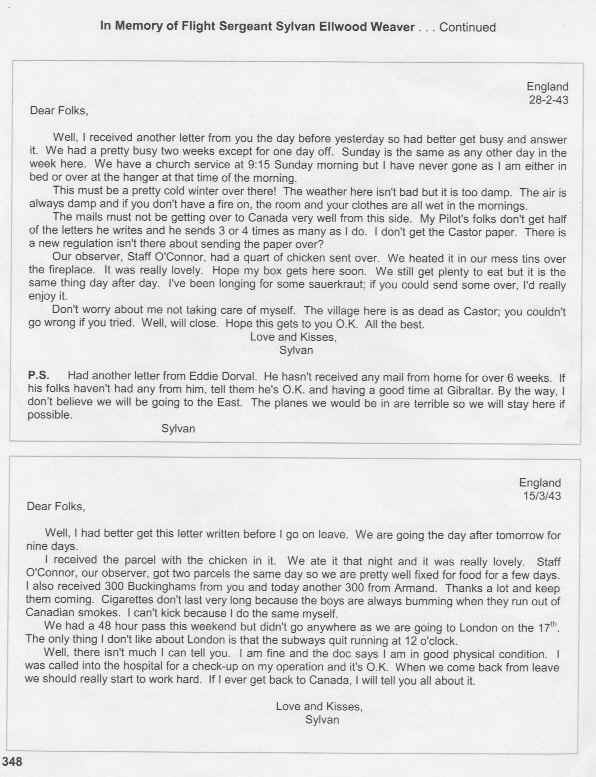

Our coming there in December of that year would be the start of operations in January '43. There were successful ones as well as numerous bad ones. During the winter months Feltwell/Methwold Squadrons continued to fly 'circus' bombing operations on France and the Low countries. 'Circus' ops were low level bombing raids with heavy RAF Fighter cover. In late February/early March 1943 the Ventura squadrons were taken off bombing operations to take part in 'Operation Spartan' a major training exercise for the invasion of Europe. The Feltwell units were to make mock attacks on 'enemy' positions within the UK. During this, March 2, a Canadian piloting a Ventura crashed near base and all were killed.

March 28, '43 l(S) took part in one of the most successful raids made by our Group 2 bombers. Our Sqn. #487 with Sqn. #464 attacked shipping at Rotterdam. 6 ships were reported damaged 3 of them with direct hits. March 29, all 3 Squadrons made two separate attacks causing considerable damage to the port installations and shipping.

April 1 - 3, ‘43 our Squadron moved from Feltwell to Methwold about 3 miles away. This new base was not as well appointed as the peacetime station at Feltwell. Diary records say: it did not take long for us to settle down and were soon agreed that it was not a bad place: after all we still visited Feltwell. Group Captain Kippenberger was still 'King of the Castle’ and that meant quite a lot. The move was completed by the evening of April 3 and in the early afternoon of the following day the squadron was able to send 12 Venturas to attack Caen aerodrome, and in the evening the same number bombed the docks and shipping at Rotterdam. l(S) was in this latter raid. We were in trouble of some kind (perhaps mechanical) but pressed forward to target to deliver our bombs. When we set out to return and had just crossed the coast of Holland flying westward, inadvertently flew over an enemy convoy. It was from this point on our flight was doomed.

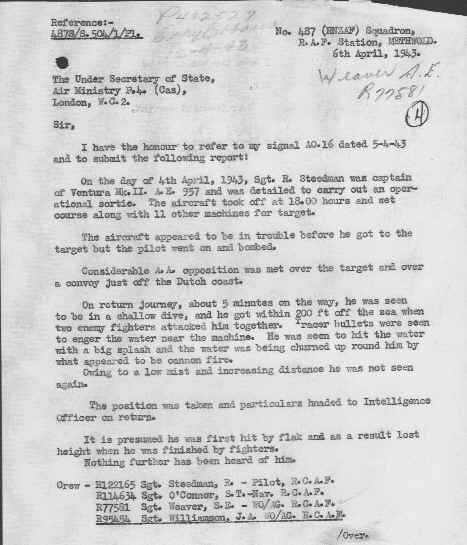

I(L) will include the letter from the Under Secretary of State of the British Air Ministry as the next page. Following that will be two pages including three letters written home. I(L) will include some comment about some of the letters. The third one March 15, 1943 was written three weeks before he was lost but probably wouldn't have been received until much later presuming mail did not go by air. Sylvan's folks were notified of his death by telegram. In his letter Feb. 28. '43 he commented that he either was in bed (not accustomed to the cold, humid climate of England winters) or over at the hangars (there had been lots of mechanical failures with the Venturas), so l(L) think there would be plenty of questions directed at the ground crews. And then the last line in that letter heralding the 'Weaver' sense of humour. His last letter sent home, March 3, ‘43 was written 2 days before he went on a 9-day leave. It appeared that he had a few trips into London. One of those may have been to the R.A.F. hospital (used for Canadian soldiers also) in Uxbridge (a borough of London) where he had been called in for a check-up on his operation.

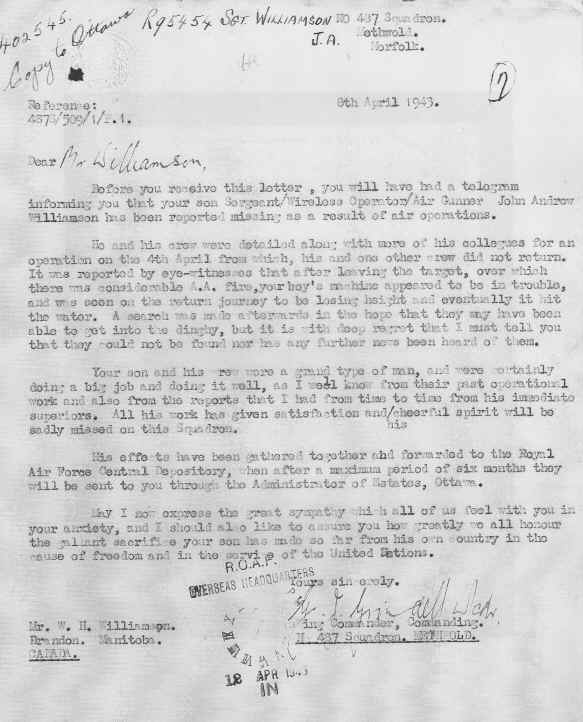

Also included here is of the letters sent to John Williamson's family as they seemed (to me(L)) to be more consolatory.

Syn. #487 stopped using Venturas after a disastrous raid on Amsterdam May 3, ‘43 in which 12 aircraft and all men except three perished. You will see that if Sylvan had not perished April 4, he may have succumbed in later raids. An interesting note: the moto of Sqn. #487 was: Ki te mutunga, which in Māori meant, 'Through to the end. The Squadron badge was a tekoteko (carved sculpture of head and body of a Māori warrior) holding a bomb.

I(L) count it a great honour to have been able to weave this account of a great man Sylvan Weaver.